There is no question that Pope Francis is a popular pontiff. He is beloved for his ecumenical openness to other non-Catholic Christians, to those of other faiths, and of no faith; for his urging of believers to go out to the highways and byways to spread the love of Christ and the truth of the Gospel; for his determination to improve the operations of the Curia; for his rejection of the more regal trappings of the papacy; for his willingness to take on controversial topics and allow unprecedented dialogue about them, and for his devotion to the Blessed Mother. Few know that Pope Paul VI shared all those qualities and in important respects paved the way for the current papacy and for the papacies succeeding his.

What distinguishes Paul VI was that he was remarkably prepared to assume the papacy, having studied and practiced Church diplomacy and having served in the higher echelons of the Curia. But really nothing could have prepared him for many of the challenges he faced.

Some of what defined Paul VI’s papacy he inherited from his predecessor, Saint John XXIII. He faced the challenge of seeing Vatican II through to completion and overseeing its initial implementation. Those were tumultuous times, times from which we are still recovering. Paul VI’s wholesale acceptance of the Mass in the vernacular mark him as thoroughly modern (though certainly not as “modernist,” as some of his critics charge). His promulgation of the Credo of the People of God in 1968 indicates that he was concerned about those who interpreted the “spirit” of the Council to suggest that virtually every teaching of the Church was up for grabs. I believe it is fair to say that the publication of the Catechism of the Catholic Church finalized the work the Credo was meant to begin if not achieve.

He also inherited the Special Commission on Birth Regulation that led to Humanae Vitae, the encyclical that has defined his pontificate (more about that soon.)

Two of Pope Paul VI’s greatest passions were ecumenism and evangelization, endeavors which have become major enterprises of the Church today. He had fruitful meetings with the Eastern Orthodox and spoke of Protestants as separated brothers and sisters and began formal dialogues with Anglicans and other Protestant denominations. The accomplishments of those endeavors are many; for instance, it is highly unlikely that the Anglican ordinariate would exist had Paul VI not begun a dialogue with Anglicans. He took the name Paul because he wanted to follow in the footsteps of St. Paul and take the gospel to the world, which led to him travelling to more foreign countries than any of his predecessors. His exhortation Evangelium Nuntiandi (1975) called the Church to a new evanglization, a call all the subsequent pontiffs have eagerly embraced.

Paul VI also had a great interest in how the Church should engage the modern world, the relationship between evangelization and dialogue (see Ecclesiam Suam 1964), as well as social justice issues—as evidenced in such key documents as Populorum Progressio (1967) and Octogesima Adveniens (1971). Indeed his passion for social justice was so great he was accused by some of being a Marxist.

There is little indication that Pope Paul VI intended his pontificate to take up questions of sexual ethics. Again, he inherited the Special Commission on Birth Regulation from his predecessor, who had appointed six priest theologians to address the question of how to present the Church’s teaching on contraception in the modern world, in anticipation of conferences at the UN on overpopulation. Paul VI, who desired to foster greater lay involvement in the Church, appointed 66 members to the commission, many of them lay. Paul VI is often criticized for not having accepted the recommendation of the commission (bolstered by the vote of 15 high-ranking Churchmen added to the commission) that the Church could change its teaching on contraception. What is rarely noted is that the commission did not have the mandate to address that question, that the commission was purely advisory, and that some person(s) broke their promise of confidentiality and released some of the documents from the commission to try to force the pontiff’s hand.

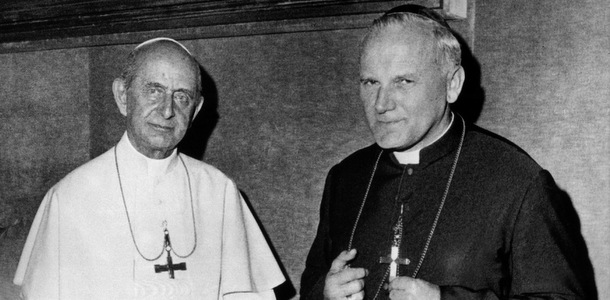

Those who insist that we must learn to read the signs of the times seem to miss that Karol Wojty?a, who was on the commission (never in attendance), sent a response to the commission documents to Paul VI and reaffirmed in personalist terms the constant teaching of the Church that contraception was not compatible with the goods of marriage. Wojty?a, who had considerable influence on the content of Humanae Vitae, did have a passion for defending it and promoting it. His Theology of the Body – written to provide a scriptural and theological basis for Humanae Vitae — has spawned a large number of projects designed to evangelize young people, those pursuing marriage and those who are married. It promises to accomplish much of the work of the new evangelization in the area of marriage and family.

The Synod began on St. Francis’ feast and is closing with a Mass that will beatify Pope Paul VI. Such timing cannot be coincidental. St. Francis was known best for his embrace of humility, poverty and chastity and for having been famously exhorted by Jesus in a vision to “repair my Church”. Pope Francis is attempting to undertake a repair of the Church, starting, it seems, with an effort to fortify marriage and the family. Marking the end of the Synod with the beatification of Pope Paul VI transparently indicates that the teaching of Humanae Vitae cannot truly be an open question, though what “pastoral accommodations” might be considered, no one knows.

In short, Pope Paul VI matters because he built on what he inherited and laid the foundation for some of the most urgent enterprises — evangelization, ecumenism, sexual morality, marriage and family — in the Church today.

…

This article appears in the Oct 9th 2014 print edition of the Catholic Herald in the UK.