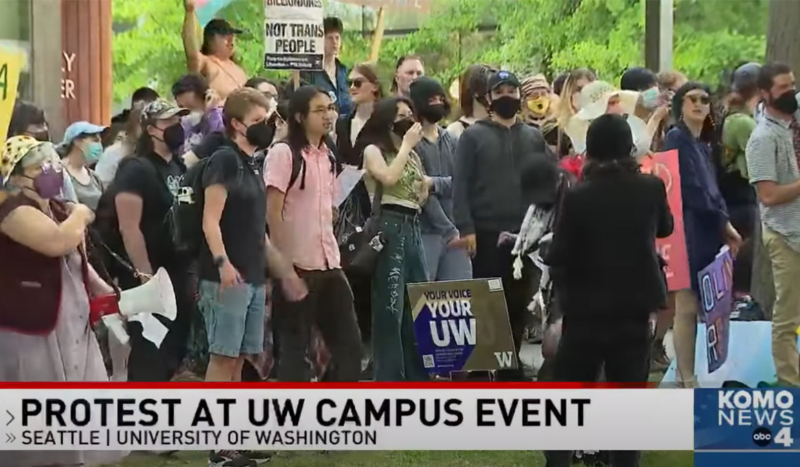

KOMO News vide screengrab

Americans’ trust in higher education has been harmed by the “heckler’s veto” – violent and disruptive campus protests against guest speakers that cause the campus to withdraw the speaker’s invitation – a California-based political science professor argued in a June 2 article.

Kevin Wallsten, an associate professor at California State University, Long Beach, wrote that Gallup polls found that the number of Americans who have “little” or “no” trust in higher education has tripled between 2015 and 2024. This decrease in trust is consistent over ethnic, political, and other subgroups.

In addition, Wallsten wrote, high school students are less trusting of higher education. The survey Monitoring the Future found that only 47% of seniors in 2023 thought that colleges are doing a “good” or “very good” job, falling significantly from 75% in 2007. Wallsten noted again that the findings were consistent across political and ethnic subgroups.

“This ‘crisis of confidence’ has unfolded alongside intensifying concerns about protest and free speech on college campuses,” Wallsten wrote. “In particular, the growing popularity of the ‘heckler’s veto’ — attempts by an individual or group to disrupt or restrict speech through excessive noise, intimidation, or violence — among college students has subjected universities to withering public scrutiny.”

Over a similar period of time as Americans’ trust in higher education decreased (2014–2024), “heckler’s veto” events have increased, according to Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression’s (FIRE) Campus Deplatforming Database.

Wallsten wrote that his post is the first to empirically connect the “veto” events with the decrease in trust for higher education.

“Drawing on an experiment embedded in a large, nationally representative survey, I examine whether exposure to video footage of a single disruptive protest aimed at deplatforming a speaker on a college campus alters how people feel about higher education,” he wrote.

In Wallsten’s experiment, there was a control group who did not see the video of disruptive students, a group who saw the video with no response from the university, a group who saw the video with a response from the university condemning the protests, and a group who saw the video with a response from the university praising the protests.

“The results are clear and striking,” he wrote “Viewing even a brief, 20-second snippet of footage showing students using the ‘heckler’s veto’ at a campus speaking event significantly worsens attitudes toward higher education among Americans from across the political spectrum.”

Wallsten also found that the university’s response to the “heckling” event does not significantly affect the viewers’ judgement of the institution.

“Whether university leaders respond by issuing statements condemning or praising the protesters does nothing to mitigate the harm caused by exposure to images of disruptive protest,” Wallsten wrote. “In other words, once the ‘heckler’s veto’ is seen, the reputational damage is done. Words from university leaders fall on deaf ears.”

He noted that the portion of respondents who had “very little” confidence in higher education was 16.1% for respondents who did not view the video and 22% for respondents who saw a video. The portion of respondents who said the institutions negatively affect “the way things are going in the country these days” was 43.3% for students who did not watch the video and 48.3% for students who did watch the video.

“Similarly, the percentage of respondents saying colleges and universities have a ‘negative effect’ on ‘the way things are going in the country these days’ increased from 43.3% among those not watching the video to 48.3% among those watching the video.”

He also found that the video of the “hecklers” negatively impacted viewers regardless of political leanings.

“Collectively, these findings challenge the widespread assumption that it is only Fox News- watching conservatives that are troubled by the growing use of the ‘heckler’s veto’ on college campuses,” Wallsten explained. “In fact, the broader public, regardless of their party affiliation and regardless of how university leaders respond, is negatively affected when it sees college students engaged in illiberal actions to stop campus speakers.”

Wallsten warned that universities that cancel controversial speakers on campus may reinforce the public’s perception that universities are not willing to defend free speech.

“If colleges and universities hope to prevent the reputational harms caused by disruptive protests, they must teach their students how to protest in ways that are peaceful, principled and, most importantly, non-coercive,” Wallsten wrote.

He pointed to several resources that can help universities and colleges embrace free speech on campus: FIRE, in partnership with New York University’s First Amendment Watch, offers free orientation modules that offer training on the difference between protests and censoring other people. Similarly, institutions like the Washington University, the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, and Appalachian State University, distribute videos about free speech on campus during the students’ orientations.

Moreover, Wallsten wrote, universities should inform students that violent and disruptive protests are ineffective, whereas non-violent protests are more likely to draw support, according to a predoctoral Harvard student’s research study of more than 300 protests since 1900.

“College students will likely always feel the impulse to protest speech they find offensive,” Wallsten concluded. “The challenge for higher education is not to suppress that impulse but, instead, to channel it into forms of expression that uphold liberal values and protect the legitimacy of the institution itself.”