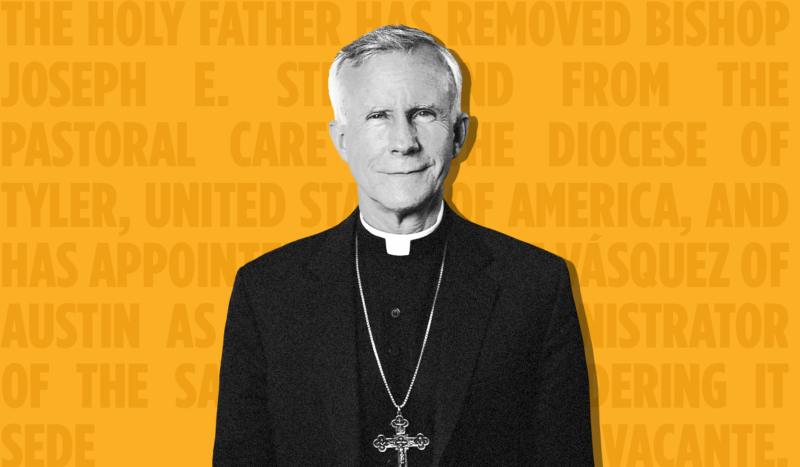

Since the Vatican and the USCCB officially announced the dismissal of Bishop Joseph Strickland from his position as head of the Diocese of Tyler, TX last Saturday, Catholics in the U.S. have been trying to make sense of the extreme measure.

Neither the Vatican nor an official statement from Cardinal Daniel DiNardo gave any justification.

Apostolic visitations of bishops (like the one the Vatican recently ordered in Tyler) and bishop removals are not frequent occurrences in the Church. They are not unheard of, however, and have become more common since Pope Francis approved the Motu Proprio “Vos Estis Lux Mundi” (“You are the Light of the World”) to streamline evaluations and punishments of bishops who have mishandled cases of sexual abuse in their dioceses.

Four U.S. bishops have resigned or been barred from ministry since the release of Vos Estis: Bishop Richard Frank Stika of Knoxville, TN, Bishop Michael Hoeppner of Crookston, MN, Bishop Michael Joseph Bransfield of Wheeling-Charleston, WV, and Richard Joseph Malone of Buffalo, NY. Pope Francis also removed Bishop Martin Holley from Memphis, TN in 2018 after a Vatican-led investigation into accusations of administrative and financial mismanagement.

Several other U.S. bishops have been investigated and cleared or are still under investigation per Vos Estis.

In all those other cases, the Vatican clearly explained its apostolic visitations and dismissals. The case of Bishop Strickland, on the other hand, is an anomaly. The Vatican-ordered apostolic visitation to Strickland’s diocese in June was secretive and remains unexplained, and the announcement of his removal was not accompanied by any explanation either.

Unlike any other U.S. bishop, Strickland has been openly critical about what he believes is Francis’ abandonment of traditional Catholic doctrine. Strickland’s critics point out not only his recent pastoral letters, but his outspokenness on social media.

He has stated on X (formerly Twitter): “I believe Pope Francis is the Pope but it is time for me to say that I reject his program of undermining the Deposit of Faith.” On YouTube, Strickland pushed back on the pope’s enthusiasm for the Synod on Synodality, saying “all this synodality is garbage as far as I’m concerned. It just is not living the truth.”

Nevertheless, both Strickland’s critics and his supporters have agreed that the final reason for his dismissal is far from clear.

Adding to the mystery is the fact that other prelates’ criticism of Francis’ magisterium – and some cases of outright disobedience – have not met with anything like the harshness of the Vatican’s actions against Strickland. Obvious examples come to mind, including progressive bishops in Germany who have openly and repeatedly defied the pope in order to pursue their women’s ordination and pro-LGBT programs.

Fr. Gerald Murray, an expert canon lawyer and commentator on EWTN’s “The World Over,” told CatholicVote on Monday that “we do not know why Pope Francis removed Bishop Strickland, because he did not give any reason for his action. That omission leads to speculations as to the reason[s], which are then taken by some to be facts.”

Murray explained that “removal is ordinarily a penal measure,” although

it can be done in the case of physical or psychological impairment. The Holy See has not published a decree for Strickland’s removal, which is required in canon law, unless the pope exempted himself from that requirement, in which case that exemption should be made by a decree. That decree should be published.

“The removal of a bishop from office without specifying if he committed a canonical crime or if he was found to be impaired offends against basic justice and charity,” Murray argued. “He is deprived office without, it seems, the benefit of due process, including an appeal, and his good name is called into question.”

On Monday, Catholic commentator Kevin Wells wrote in an opinion piece at Crisis Magazine that Strickland’s removal was his “punishment” for pleading with fellow U.S. bishops at a 2018 meeting in Baltimore to act more boldly against the sexual abuse crisis and its roots in homosexuality and sexual permissiveness.

“A number of high-powered cardinals and bishops had kept silent about (former Cardinal Theodore) McCarrick for years,” Wells pointed out:

And many of those same men had just been told by the uncelebrated, small-town bishop that inviting Fr. James Martin into their diocese was opening the door to scandal. Many of the bishops in the room that day had already warmly invited Fr. Martin in, helping him to become one of the most well-known priests in the world.

Francis’ handling of other, in some cases much more controversial bishops stands in sharp contrast to the swift and decisive treatment Strickland has received.

Consider the case of Bishop Gustavo Oscar Zanchetta, an Argentine bishop and close collaborator with Francis.

Francis named then-49-year-old Zanchetta as bishop of Orán, Argentina in 2013. Francis then appointed Zanchetta assessor of the Vatican’s central financial institution in 2017 after the bishop resigned from his diocese for alleged health reasons amid widespread accusations of financial mismanagement and sexual abuse in his diocese.

Francis was combative in response to the considerable scrutiny he faced over what critics called his indulgent treatment of Zanchetta.

“There had been an accusation and, before asking him to resign, I had him come here immediately with the person who accused him,” Francis said in 2019. “In the end, he defended himself by saying that his cell phone had been hacked.” Francis suggested it was ordinary and appropriate practice not to jump to conclusions and to give Zanchetta the benefit of the doubt.

Regarding the financial accusations against Zanchetta, Francis said the matter was “not entirely clear” and had “not been proven.”

When clergy made formal complaints to the nunciature, Francis said, “I called the nunciature, and the nuncio said to me: ‘Look, the issue of reporting abuse is serious….’” Francis called for Zanchetta and “asked him” to renounce his alleged misconduct before sending him to Spain for psychiatric examination.

Francis sharply criticized reports that his response to complaints against Zanchetta was circuitous and lacking in urgency.

“Some media have said ‘The pope gave him a holiday in Spain.’ But he was there to do a psychiatric test,” Francis said. Despite his faults, Zanchetta had “skills” as a manager and consultant that Francis believed made him worth keeping around, the pope argued. “Some have interpreted it here in Italy as a ‘parking lot,’” Francis said of the controversial prelate’s haven near the pope. “He was messy, but the vision was good.”

Zanchetta was only dismissed in 2019 after a long canonical process. He was also sentenced to four and half years in jail for sexually abusing seminarians.

Has the dismissal of Bishop Strickland been a case of sheer doctrinal revenge?

In an article published in June following the apostolic visitation to Strickland, the Catholic News Agency referenced other visitations and dismissals that took place first in Paraguay and later in Puerto Rico.

In the diocese of Ciudad del Este in Paraguay, Francis removed Bishop Rogelio Livieres Plano on September 25, 2014.

Originally ordained a priest of Opus Dei in 1978, Bishop Livieres had led the Diocese of Ciudad del Este since 2004. Soon after his appointment, the Argentinian-born Livieres started promoting priestly vocations and opened his own seminary, separate from Paraguay’s Interdiocesan seminary. In a decade, he ordained more than 60 priests.

Livieres’ trouble started when the rest of the Paraguayan episcopate complained that his seminary broke the “collegiality” of the episcopate.

In 2012, Archbishop Pastor Cuquejo accused Livieres of accepting into his diocese an Argentinian priest, Fr. Carlos Urrutigoity, and appointing him as his vicar general despite the priest’s history of sexual abuse accusations involving minors in the Diocese of Scranton, NJ.

Fr. Urrutigoity had been suspended by then-Bishop of Scranton James Timlin.

The accusation came four years after Livieres recognized his “imprudence” and dismissed the priest in 2008, several years before the apostolic visitation.

Among the reasons that Livieres gave for starting his own seminary was what he described as a pervading “homosexual culture” in the Catholic Church in Paraguay. In a remarkable statement during a press conference, he accused his accuser, Archbishop Cuquejo, of being a practicing homosexual himself.

As in the case of Strickland, the Vatican requested that Livieres resign, and he refused. Livieres was sacked and replaced after the apostolic visitation, which took place in July 2014.

The Vatican released a statement (now removed from the official Vatican website) that explained that the removal of Livieres “was a difficult decision on the part of the Holy See, taken for serious pastoral reasons and for the greater good of the unity of the Church in Ciudad del Este.”

The Vatican’s statement added:

The Holy Father, in the exercise of his ministry as the “perpetual and visible foundation of the unity of both the bishops and the multitude of the faithful”, asked the clergy and all the People of God of Ciudad del Este to accept the Holy See’s decision with a spirit of obedience and docility and without prejudice, guided by faith.

Livieres responded to the announcement with his own letter addressed to the then-Prefect of the Congregation of Bishops, Cardinal Marc Ouellet, stating that he had refused to sign a resignation letter “on his own initiative, thus wanting to testify to the end of the truth and the spiritual freedom that a Pastor should have.”

In his letter, Livieres said that he had always been

in communion with all the Popes and I will always continue to be. Even when it was my turn to agree to the decision of my dismissal as Bishop. And this despite the fact that, personally and in the judgment of my conscience, I consider this decision to be procedurally unjust, unfounded regarding the substance of the case, arbitrary and an attack against the legitimate authority that God has given to the Bishops as successors of the Apostles.

Livieres died of liver failure in his native Argentina on August 14, 2015, at age 69.

The other case of an unexplained dismissal by the Vatican is far more recent: Pope Francis removed Bishop Daniel Fernández Torres from the Diocese of Arecibo on March 9, 2021. The bishop was 57 years old at the time.

The Chicago-born bishop was known also for sending his numerous priestly vocations to the Theological faculty of the University on Navarre, Spain, run by Opus Dei, rather than to the interdiocesan seminary of Puerto Rico.

He supported the right of Catholics to conscientious objection to compulsory COVID-19 shots in a statement published on August 17, 2021. He then refused to sign a joint statement issued on August 24 by the Puerto Rican bishops, which said in part that “there is a duty to be vaccinated and that we do not see how a conscientious objection can be invoked from Catholic morality.”

Fernández Torres openly opposed gender ideology, which he described as “religious persecution” against Christians and a violation of parental rights.

Following the visit of Chicago Cardinal Blase Cupich, which was never presented to him as an apostolic visitation, Fernández Torres’ dismissal was announced by the Vatican without any explanation.

In a public letter addressed to “the People of God” in Arecibo, Fernández stated that

when you receive the news of my replacement as bishop at the head of the diocese of Arecibo, I want you to know that it is not my place to explain to you a decision that I cannot explain myself, even if I accept it with the patience of Christ for the good of the Church.

“I deeply regret that in the Church where mercy is so much preached, in practice some lack a minimum sense of justice,” the Puerto Rican bishop added, explaining that “no process has been made against me, nor have I been formally accused of anything and simply one day the apostolic delegate verbally communicated to me that Rome was asking me to resign.”

“A successor of the apostles is now being replaced without even undertaking what would be a due canonical process to remove a parish priest,” he wrote.

Fernández also revealed that

I was informed that I had committed no crime but that I supposedly “had not been obedient to the pope nor had I been in sufficient communion with my brother bishops of Puerto Rico.”

It was suggested to me that if I resigned from the diocese I would remain at the service of the Church, in case that, at some time I was needed in some other position; an offer that in fact proves my innocence.

“However,” he said, “I did not resign because I did not want to become an accomplice of a totally unjust action and that even now I am reluctant to think that it could happen in our Church.”

Echoing Fernández, Strickland told LifeSiteNews after his own removal: “I stand by all the things that were listed as complaints against me.” In particular, he pointed out that “I know I didn’t implement Traditiones Custodes (the pope’s 2021 restriction of the Traditional Latin Mass) because I can’t starve out part of my flock.”

A Catholic group is inviting Strickland’s supporters to attend a Rosary procession on Saturday, November 18, in front of the Diocese of Tyler’s chancery office.

In a social media post responding to the planned event, Strickland wrote:

I pray that this effort is prayerful, respectful and focused on Jesus. He is the only support I need and I feel the profound embrace of His Sacred Heart. I appreciate the vigorous faith this is inspired by but please remember I am nothing, Jesus is everything.